Guru-Shishya Parampara

I do not believe it is possible to learn or teach Indian Classical Music properly unless the guru-shishya (teacher –student) tradition is followed. In this tradition, the shishya must immerse him or herself in the company of the guru for an extended period of time. The shishya should spend their time observing the guru’s actions watching how the guru explains, sings and plays his music. This

immersion is necessary for the disciple to absorb the essence of our music and the light of his or her guru. Until this happens, one cannot learn properly.

I had two relationships with my father; one of father and son and the other of guru and shishya. I was with my guru constantly. He would teach me about music, raag and taal, and also about how things in life are connected to and flow back into music.

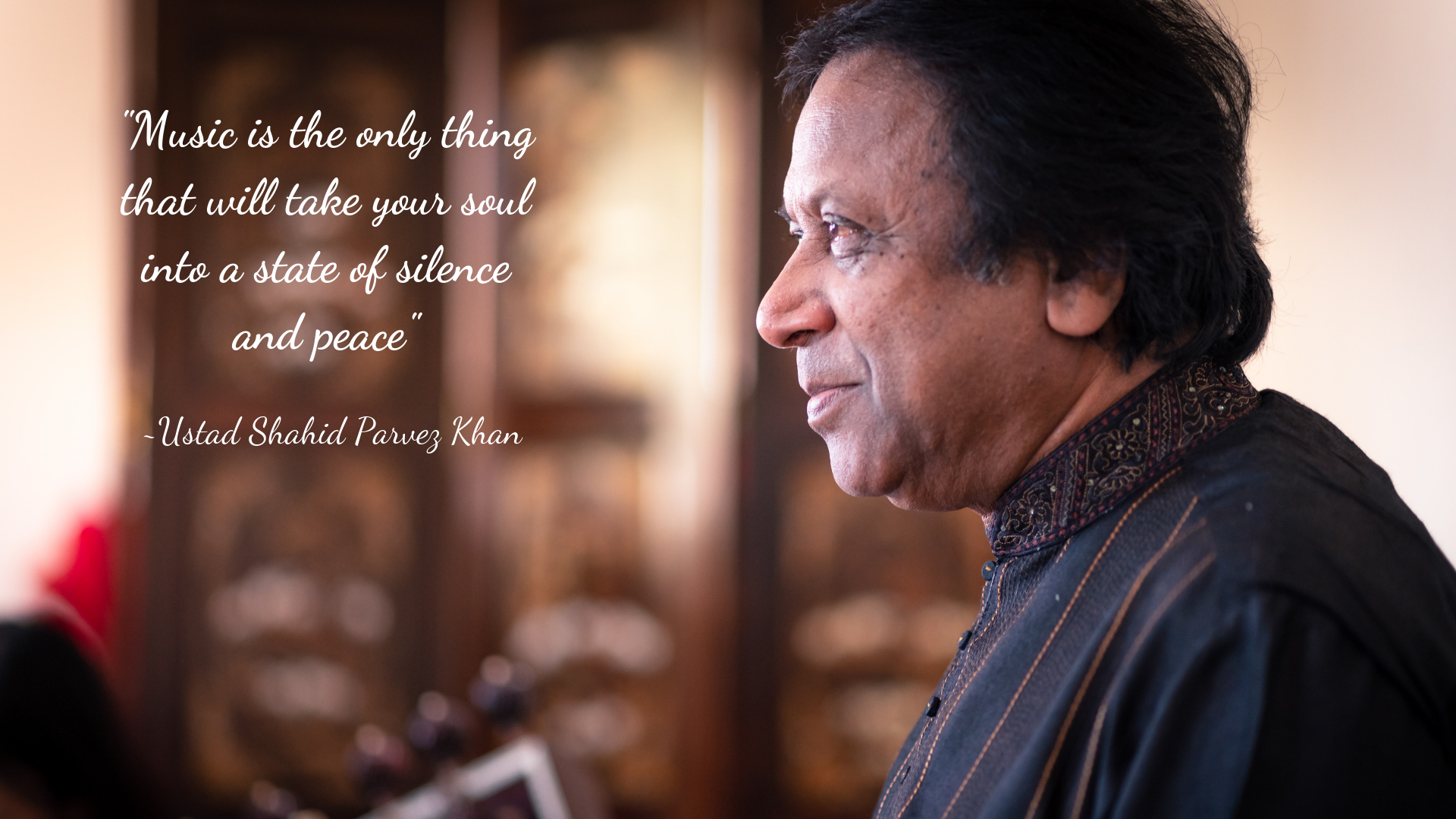

Known simply and lovingly as Ustad ji to his students around the world, Ustad Shahid Parvez proudly upholds this ancient guru-shishya tradition as just one of his ways of spreading music.

On the definition of a raag

Over the years, musicians and scholars have defined raags in several ways. A raag is neither a mood nor a melody. A raag is however, an esthetic form with a precise and scientific basis – It is a melodic framework forged by tradition and tempered by countless expositions by generations of master musicians. Each raag does intrinsically carry with it some emotional content or we can say that it lends itself to a certain mood. The mood encapsulated by a raag is called its rasa. Each raag is also associated with time of day and some are even associated with seasons.

Canonically put, a raag is a combination of notes (sur) with specific rules around ascent and descent. However, since our music is based on generations of empirical development, one must learn and listen to performances of the same raag by many different masters. Even though the palette of surs and rasa may be the same, two masters will often paint different pictures of the same raag. To learn a raag from one master is often not enough as only one picture is presented.

In Indian Classical Music, melody is created within the framework of the raag. When music is played with the intent of being in the Indian Classical genre, it is of paramount importance that it be presented in raag.

On creating new raags

So many raags already exist – thousands of them, I do not believe there is much scope to create many more. In my opinion, creating a raag is not such a great accomplishment. There are occasions when musicians do happen upon new combinations. There is no harm in inventing a raag, but I do not believe in purposely investing all of oneself in doing so.

It does happen sometimes though. Once, I was invited to perform at around 2:30 am. Since it was the cusp of night and day, I contemplated on what might be appropriate. It felt like neither night nor day. Suddenly a composition leapt to mind that combined Bhinna Sharaj and Lalit – so I named it Bhinna Lalit. It is a combination of two distinct raags, like the end of one night meeting a new morning.

On the role of music in my life

I was given a sitar a very young age. At first I thought it had been forced upon me but very soon I realized that I was made to play sitar. Music is not my profession, it is my life. I don’t believe I can live a better life than this. Music is the most fantastic thing in the world – it is meditation, it is entertainment, it is art, it is wealth – it is a treasure that no one can take from you until you decide to share it. It is tremendously precious.

Music is my most beloved. I love nothing more than music.

The invention of the sitar and its inventor

The invention of the sitar and its inventor are both rather controversial topics. According to the forefathers of our gharana, the Etawa gharana, it is generally accepted that the sitar was invented by Hazrat Amir Khusro around the 15th century. The name sitar is derived from the Persian word seh-tar - meaning an instrument with three strings. It is believed that when the sitar was created, it only had three strings. Over the years, the sitar instrument changed gradually – the number of strings was increased, sympathetic strings were introduced and frets were added. Due to these changes the sound of the sitar also changed.

The gharana one belongs to will determine the number of strings and frets used in its sitar. In the Etawa tradition, there are six main playing strings, eleven sympathetic strings, and twenty frets. Nonetheless, this may still vary according to the musician’s individual playing style. For example, even in the Etawa Gharana there were seven playing strings until Ustad Vilayat Khan Sahib refined it to six. A lot of people now refer to the six string sitar as the Vilayat Khan style.

On raag exposition

In our music, be it vocal or instrumental, a raag is developed through several movements that are presented in sequence. In instrumental music, the following movements are presented.

The first movement is the Alap. It is a slow, serene movement without the accompaniment of rhythm. It is the initial invocation and in it a raag is unfolded note by note. It is slow in speed but must be meaningful. It should present a clear picture of the raag, expressing its mood and conveying its emotion. Simply playing something in slow speed cannot be defined as Alap.

The second movement, known as the jor alap, introduces the element of an overt rhythmic pulse. It has a tempo but is not in any rhythm cycle (taal). The final unaccompanied movement is the jor jhalla. In this up tempo movement, the chikaris (top two strings) are used extensively.

At this point, the solo movements end and the accompanying percussion instrument, the tabla, is introduced. The accompanied movements are exposed through compositions called gats which are set to various rhythm cycles (taals). The artists start in slow tempo (vilambit), gradually building to medium (Madhya) and fast (drut) gats.

On Good Music

I don’t mind whether the music is classified as light, Indian classical or Western classical - I just love to listen to good music.

On Music

The most important thing in music must be sur, but rhythm too is paramount. To me everything is about the right combination of the two elements. People generally give one more prominence, and sadly at the other’s expense. Music is about being melodious and soulful.

Often a musician’s preference will be determined by his or her temperament. Some artists are sensitive to sur only and assume that the addition of more rhythmic patterns will spoil the music or raag – I disagree with this notion. True musicality implies sensitivity to melody and rhythm. The creation of music is the graceful marriage of both elements.

If a musician’s temperament is not of a rhythmic nature, the cure is to work on rhythm that much harder. Without rhythm, music is incomplete

On music and spirituality

Music is the door to spirituality. It is the best possible way to embrace spirituality. Sufis, ascetics, sadhus – all spiritual people use music to meditate. Music is the only thing that will take your soul into a state of silence and peace. It makes a person more sensitive and receptive to the world. When a musician plays, music flows through him from another source. The musician reaches a certain level when it is not just he who is playing – he is a vessel, a channel through which a higher being speaks.